What itâs like to support the WGA strike as an aspiring union member

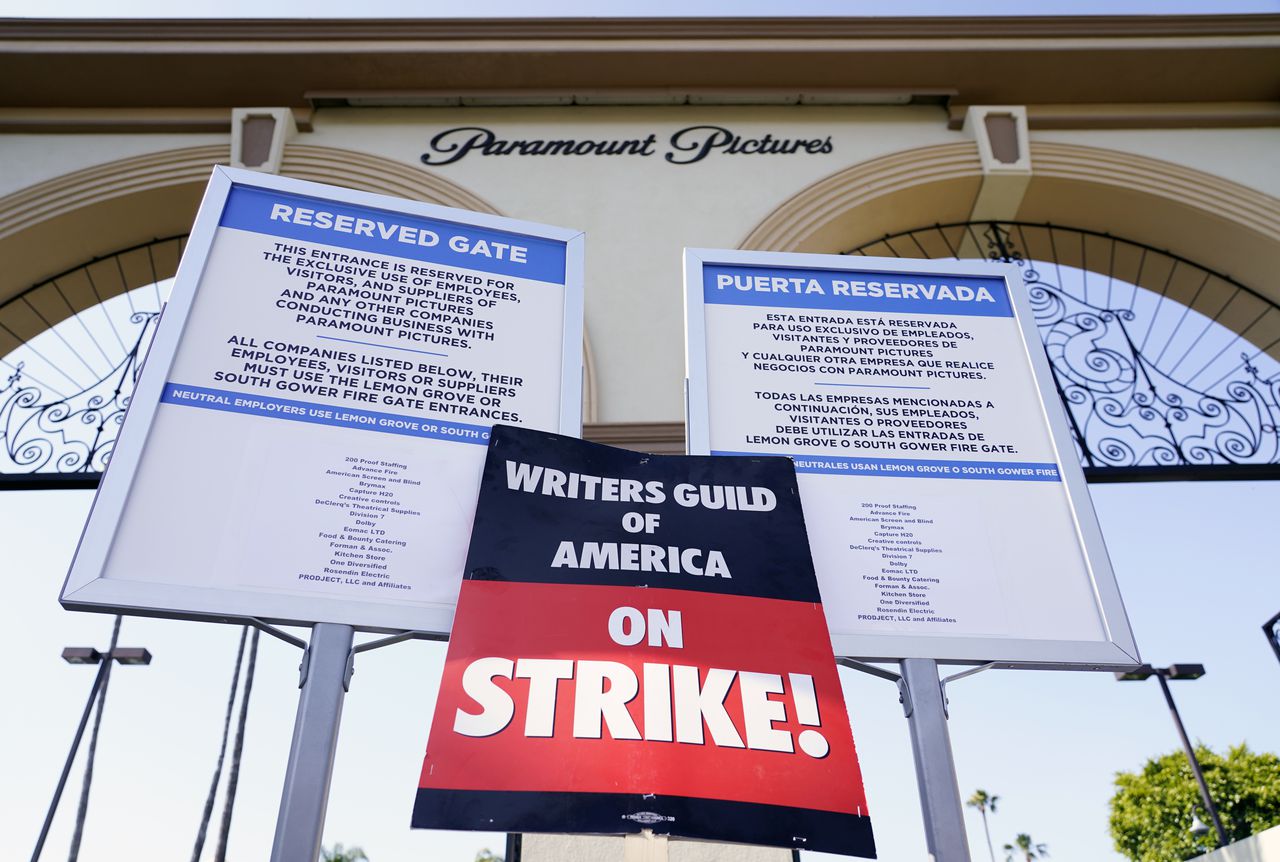

As the Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike enters its second week, there’s been many non-WGA members who’ve joined the fight.

Non-guild members, also known as pre-WGA writers, have had to walk away from opportunities and deals offered by studios the WGA is striking against, or they can never be allowed to join the WGA as a member forever.

Pre-WGA writer Melanie Fierstein acknowledges how tough that sounds.

“I was in the middle of a potential TV deal when the strike hit. And that TV deal would have been the thing that let me join the WGA,” she said.

But that hasn’t stopped her from going down to the picket lines almost every day, as she fights for her “future rights.”

“It’s just really inspiring to see a bunch of writers betting on themselves and saying, theoretically, I could take a job but I’m not going to,” she said. “Because I want to support the deal that [the WGA is] fighting for that will end up making me more money and protecting my career.”

Becoming a member of the WGA is what many writers like Fierstein aspire to achieve because it offers security and protection for writers working in a very unstable industry.

“To be honest, the only way to get health insurance is through the guild,” said WGA captain Eli Edelson, along with legal protections and a pension plan, among other things.

“[Hollywood] is very unstable. It’s a very freelance lifestyle,” said Edelson. “And even once you’re in the guild, it’s still on you to get staffed on the next show or to sell your next feature screenplay.”

But at least the guild can offer you protection, healthcare and a pension, said Edelson. “Which, for a long time, was never a thing for writers in Hollywood. So, it does offer a sense of stability and backing that a lot of folks wouldn’t have otherwise,” he said.

This is, arguably, the promised land for many writers in Hollywood. But strikes can make it tricky for pre-WGA writers.

“A lot of studio heads will try to hire pre-WGA writers to kind of prey on their desperation,” said Fierstein. “Or talk them into thinking that it’s their opportunity now, because WGA writers can’t take jobs.”

Under strike, pre-WGA writers would also be prohibited from future WGA membership if they take work from a company that’s owned by a struck studio.

“And it’s really tough, especially for a lot of younger writers who don’t have any representation or an attorney to help guide them,” said Fierstein. “It’s a really tricky thing being that there is no official guidance for pre-WGA writers and no official protections.”

That’s what Edelson hopes to change through this strike.

A lot of pre-WGA writers end up having to work with producers who are willing to hire them because they can undercharge non-guild members.

During the weeks of negotiations leading up to the WGA strike, “it was all about addressing how [writers] rooms have been changed to be exploitative, and how we can reset them or at least increase compensation for the fact that it’s become more and more unstable,” added Edelson.

By pre-WGA writers withholding their content and not selling their work to producers and studios, they stand in solidarity. “That way, the strike will be over that much sooner,” said Edelson.

Therefore, the changes they’re fighting for apply to them. “There’ll be more opportunities for pre-WGA to be able to join the guild because there’ll be bigger [writers] rooms and the rooms will be more stable and pay better,” said Edelson. “So, it benefits all of us in the long run.”

While choosing not to work in the short term can seem frustrating, pre-WGA writers like Fierstein understand that it would have been more frustrating for her in the long term.

“It’s protecting my future instead of trying to take the sparkly thing that’s in front of you,” she said. “You bet on yourself and say, I think I’m worth more than that.”